Solid-State Batteries: What’s Real in 2026 and What’s Still Labware

Why this matters this week

If you own or architect anything that depends on lithium-ion—EVs, stationary storage, or fleet charging—solid-state batteries (SSBs) have moved from “hand-wavy slideware” to “you should start modeling scenarios.”

The critical shift is timeline compression: we’re no longer talking “post-2035.” Multiple vendors are now:

- Shipping pilot production cells to OEMs.

- Locking in factory tooling and supply contracts.

- Committing to specific pack-level energy density and cycle life targets.

This doesn’t mean 2027 mass-market solid-state EVs are guaranteed. It does mean:

- Long-lived infrastructure (charging, depots, grid storage) you design now may be mis-optimized if you assume today’s lithium-ion constraints for 15+ years.

- BOM and form-factor decisions in platforms launching 2028–2030 are being made this year.

- Supply-chain and reliability risks look very different when you swap flammable liquid electrolytes for ceramic or polymer solid electrolytes.

If your job involves TCO models, grid capacity planning, or EV product roadmaps, you should have an explicit position on SSBs: what you assume, why, and how you’ll update.

What’s actually changed (not the press release)

A few concrete, 2025–2026 shifts that matter beyond marketing slides:

-

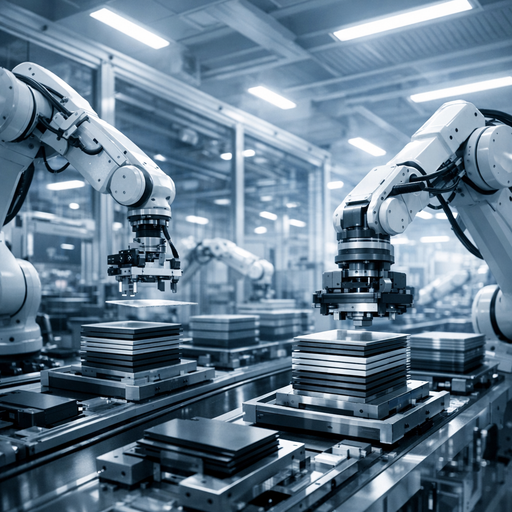

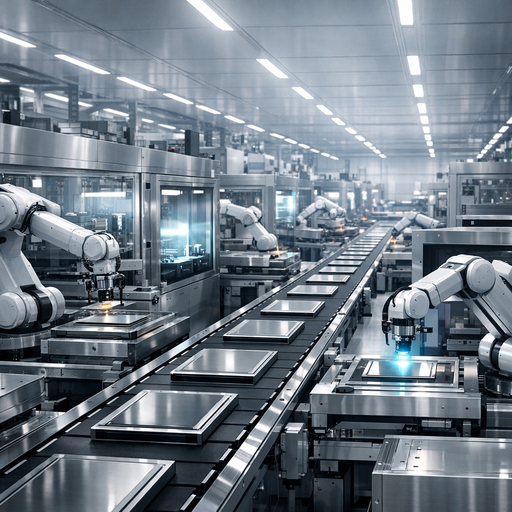

Pilot manufacturing lines are real, not renders

- Several vendors (Japan, Korea, US, EU) now have pilot lines producing tens of MWh/year of solid-state cells for automotive sampling.

- These lines:

- Run at seconds-per-cell, not minutes.

- Use modified versions of existing Li-ion tooling for at least some steps (calendering, stacking).

- Yields are still low (20–60% is a realistic range from people close to manufacturing), but that’s a step up from “only works in coin cells.”

-

Automotive OEMs have locked in first integration targets

Patterns across multiple OEMs (ICE-to-EV and EV-native):

- First SSB integrations are premium trims and performance variants, not entry-level EVs.

- Targeted benefits:

- ~30–50% pack-level energy density uplift vs today’s NMC packs.

- Similar or slightly better cycle life (1,000–2,000 full cycles to 80%).

- Faster charging (3–4C bursts) if thermal and dendrite issues cooperate.

- Launch windows whispered in vendor and OEM roadmaps are 2028–2030 for limited volume models.

-

Chemistry convergence is emerging

While press releases parade everything (sulfides, oxides, polymers, hybrids), a few patterns:

- Sulfide solid electrolytes: Leading the pack for near-term automotive because:

- High ionic conductivity.

- Processable at reasonable temperatures.

- Oxide (e.g., garnet-type) electrolytes: Better chemical stability, tougher mechanical properties, but harder to manufacture at scale right now.

- Polymer or hybrid systems: Often “semi-solid” or “gel-like,” sometimes marketed as solid-state. These may hit earlier but with more modest gains (think safety and packaging, not 2x energy density).

Rough takeaway: early commercial solid-state EV packs are likely sulfide-based, pouch or stacked formats, with careful operating envelopes.

- Sulfide solid electrolytes: Leading the pack for near-term automotive because:

-

Safety evidence is accumulating, but incomplete

- Abuse tests (penetration, crush, overcharge) on some SSB prototypes show:

- Strong reduction in runaway propagation across cells.

- Lower risk of fire vs flammable liquid electrolyte packs.

- But:

- Many cells still contain flammable binders, current collectors, and packaging.

- A handful of failures in early field tests have produced thermal events, though typically less catastrophic.

The realistic framing: SSBs are safer than conventional Li-ion, not magically “non-flammable.”

- Abuse tests (penetration, crush, overcharge) on some SSB prototypes show:

-

Grid storage implications are now in internal planning decks

Several utilities and IPPs are:

- Running storage RFPs with explicit “post-2030 solid-state compatible” language.

- Modeling containerized SSB-based systems with:

- Higher energy density per footprint.

- Better safety in urban / indoor deployments.

- Potentially improved partial-state-of-charge durability.

No one is signing pure solid-state grid storage PPAs yet, but it’s in serious long-term planning, not just R&D.

How it works (simple mental model)

You don’t need deep electrochemistry; you need a few mental hooks to reason about architecture and risk.

Think of a solid-state battery as:

A standard lithium-ion cell with the liquid electrolyte and separator replaced by a solid material that moves lithium ions, plus some re-optimizations of electrodes.

Key components:

- Cathode: Often similar to today’s (NMC, high-nickel, sometimes LFP or high-voltage variants).

- Solid electrolyte: Ceramic, glass, polymer, or composite that:

- Conducts lithium ions.

- Blocks electrons (you still want the cell to be an insulator between electrodes).

- Provides some mechanical structure.

- Anode:

- Either a conventional graphite/silicon-type composite (easier).

- Or lithium-metal (the “holy grail” high-energy option, but with dendrite risks).

Core differences vs conventional Li-ion:

-

No bulk liquid electrolyte

- Less flammable material.

- Ion transport happens through a solid lattice or polymer matrix.

-

Interface is everything

The solid–solid interfaces (cathode–electrolyte, anode–electrolyte) control:

- Impedance.

- Cycle life.

- Dendrite formation.

- Mechanical stress under charge/discharge and temperature swings.

Manufacturing has to make these interfaces thin, uniform, and free of voids.

-

Mechanical and thermal behavior matters more

- Solids crack, delaminate, and form voids.

- Stacking pressure, compressive fixtures, and thermal expansion coefficients become design parameters just like C-rate.

A simple mental model:

- Better energy density and safety are paid for with harder manufacturing and more sensitive interfaces.

- Early commercial SSBs will behave like “better Li-ion with quirks”, not like a completely different storage category.

Where teams get burned (failure modes + anti-patterns)

Patterns from automotive and stationary teams starting to integrate “next-gen” batteries:

-

Roadmap anchoring on marketing numbers

Anti-pattern:

- Product roadmap assumes:

- “2x energy density by 2028”

- “10-minute 0–80% charging”

- And bakes those into:

- Vehicle range promises.

- Charger power specs.

- Depot electrical infrastructure.

Reality checks:

- Pack-level energy density improvements more likely in the 30–70% range initially.

- Fast charging limited by:

- Thermal constraints.

- Dendrite risk at high current densities.

- Grid and cable limits at the system level.

- Product roadmap assumes:

-

Assuming drop-in compatibility

Failure mode:

- Treating SSB packs as physical and electrical drop-in for Li-ion:

- Same pack form factor and clamping system.

- Same BMS algorithms.

- Same cooling architecture.

What actually happens:

- SSB modules may require:

- Constant stack pressure within tight tolerances.

- Different operating temperature windows (some chemistries like slightly elevated temps).

- Different SOC limits and resting behavior to avoid interface degradation.

- Treating SSB packs as physical and electrical drop-in for Li-ion:

-

Ignoring supply-chain and geopolitical constraints

Anti-pattern:

- Business case assumes:

- SSB pack costs follow similar learning curves to Li-ion.

- Materials and tooling ramp smoothly.

Missed realities:

- Solid electrolytes use:

- Different lithium salts.

- Sometimes scarce elements (e.g., germanium in some sulfide systems).

- Manufacturing tools are not yet fully commoditized; vendor lock-in risk is high.

- Yield ramp from 20% to 90% is not guaranteed on a nice S-curve.

- Business case assumes:

-

Security and safety assumptions lag chemistry

For grid and fleet operators:

- Treating SSB containers as “non-hazardous”:

- Relaxed monitoring.

- Less stringent fire suppression.

- Underestimating:

- What a worst-case cell failure looks like.

- Data you need from the BMS to detect pre-failure conditions in solid interfaces.

- Treating SSB containers as “non-hazardous”:

-

Overfitting to a single vendor’s architecture

Example pattern:

- One OEM locks deeply into Vendor A’s sulfide-based SSB:

- Pack mechanicals tuned to specific stack pressure.

- BMS models tuned to their impedance and degradation profile.

- When Vendor A slips, switching to Vendor B (oxide-based, different voltage and temp profile) is nearly a full re-architecture.

- One OEM locks deeply into Vendor A’s sulfide-based SSB:

Practical playbook (what to do in the next 7 days)

You can’t force the chemistry timelines, but you can harden your assumptions and systems.

1. Make your assumptions explicit

Write down (1–2 pages, max):

- Earliest year you assume:

- SSB option for a flagship EV.

- SSB option for grid or behind-the-meter storage in your region.

- Expected:

- Pack-level energy density improvement range (e.g., +30–60%).

- Charging rate improvements (e.g., sustained 2–3C, not marketing peaks).

- Cost trajectory:

- When you assume $ per kWh parity with advanced Li-ion.

Have engineering, product, and finance agree this is your baseline and define triggers to update (e.g., first large-volume factory reaching >70% yield, first >10 GWh/year contract signed).

2. Make architectures chemistry-flexible where it’s cheap to do so

For EV or pack designers:

- Leave margin in:

- Module dimensions and pack cavity to tolerate different aspect ratios or densities.

- Cooling layouts that can adapt to different temperature windows.

- Mounting and clamping to accommodate packs requiring controlled stack pressure.

For grid/storage integrators:

- Design containers and racks with:

- Some flexibility in module footprint.

- Cooling/fire-suppression systems that don’t assume a specific cell type.

- Data and power wiring that can handle different voltage windows per module.

3. Update your TCO and infra models with SSB “shadow scenarios”

For:

- Fleet operators / depot planners.

- Utilities / microgrid designers.

- Charging network architects.

Add at least two shadow scenarios to your models:

- **Conservative