Solid-State Batteries Are Getting Real, But Their Constraints Are Brutal

Why this matters this week

If you build or bet on electric vehicles, grid storage, or anything that touches large-scale electrification, solid-state batteries (SSBs) are no longer a distant R&D curiosity. They’re creeping into the uncomfortable “you have to form an opinion now” phase.

In the last few weeks:

- Another major automaker confirmed a specific solid-state EV launch window (late decade, with pilot production lines already under build-out).

- Multiple solid-state players quietly shifted from pure sulfide chemistries to hybrid or polymer-ceramic approaches to hit manufacturability and safety targets.

- A few grid-scale storage projects have started evaluating SSBs for high-temperature or “nasty environment” use cases where safety and form factor beat kWh price.

The net: if you’re making long-lived infrastructure bets (5–15 year horizons) or building products around EV platforms, you need a realistic view of:

- Timelines: when these chemistries might actually be in volume production.

- Manufacturing constraints: where the yield and capex landmines are.

- Performance envelopes: where SSBs are strictly better than today’s lithium-ion, and where they’re overrated.

This isn’t about “the future of mobility.” It’s about not committing to architectures (thermal management, pack layout, charging infrastructure, grid interconnects) that will age badly when higher energy density and different safety envelopes arrive.

What’s actually changed (not the press release)

Skip the marketing. Mechanically, these are the meaningful shifts:

1. Pilot lines are real, not slideware

We’ve moved from lab coin cells to pilot lines that:

- Run partially continuous processes (not all glovebox batch work).

- Produce multi-Ah cells with repeatable cycling results.

- Have early yield data (still ugly, but non-zero) under quasi-production conditions.

The interesting reality checks:

- Yields on early solid-state lines are often in the single digits to low tens of percent.

- Defect modes are dominated by mechanical issues (cracks, delamination, pinholes) rather than pure electrochemistry.

- Tool vendors are being asked for micron-level precision at battery-factory speeds, and they’re not fully ready.

For a CTO thinking about cost per kWh, this means early units will look like aerospace-grade hardware: technically impressive, economically painful.

2. Cathode loading and energy density are clarifying

The press releases trumpet “2x energy density.” The reality:

- Many current SSB prototypes land at 20–40% higher gravimetric energy density vs. good NMC Li-ion, not 100%.

- Volumetric energy density gains are often better (solid-state allows tighter packing), but only if mechanical stack tolerances are hit.

- The biggest wins come if you actually ship lithium-metal anodes, which are still the riskiest part of the system.

So: you likely get meaningfully better pack-level Wh/kg, but you don’t get magic. Pack engineering still matters.

3. Thermal and safety envelope is materially different

Compared to conventional liquid electrolyte lithium-ion:

- SSBs are substantially more tolerant to thermal abuse and puncture.

- Combustible solvent is reduced or eliminated, lowering runaway risk.

- But: the interfaces (lithium/solid-electrolyte, cathode/solid-electrolyte) can still locally heat and fail in interesting ways, just with less dramatic fires.

For EV and grid architects, this has cascading implications:

- You can relax some module-level safety overhead (less spacing, lighter containment).

- You might simplify or redesign thermal management (fewer or differently placed cooling channels).

- But you still need robust monitoring because early SSBs may fail more unpredictably while manufacturing matures.

4. Realistic timelines are converging

If you aggregate recent statements and actual capex:

- 2025–2027: Limited-volume cells in niche products (premium EV trims, aviation, specialized industrial).

- 2028–2030: First mainstream EV models in select markets, still with price premiums or limited configurations.

- Post-2030: Potential for SSBs to be standard in higher-end platforms; broader grid use if cycle life and cost targets are met.

This assumes:

- Pilot lines reach reasonable yield (50–70%+).

- Tooling and process control get debugged.

- Lithium supply and solid electrolyte precursor costs don’t explode.

If you build 10+ year products, you can’t ignore this curve.

How it works (simple mental model)

A minimal engineer’s model for solid-state batteries:

-

Replace liquid electrolyte

- Today’s Li-ion: porous separator soaked in liquid organic solvent with dissolved lithium salt.

- SSB: a solid electrolyte layer (ceramic, polymer, or composite) that:

- Conducts lithium ions.

- Physically separates anode and cathode.

-

Target lithium-metal anode

- Conventional cells: graphite (or silicon-graphite) anode; energy density limited by host structure.

- SSB goal: thin lithium-metal foil anode or “anode-free” designs (lithium plated from cathode during formation).

- This is where most of the promised energy density gain comes from.

-

Interfaces are everything

The critical challenges are at interfaces:- Li / solid-electrolyte interface: mechanical contact, dendrite suppression, interphase formation.

- Cathode / solid-electrolyte interface: chemical stability, volume change tolerance, void formation.

Think of it like trying to keep multiple ultra-thin, brittle layers perfectly bonded while they breathe, swell, and shrink thousands of times.

-

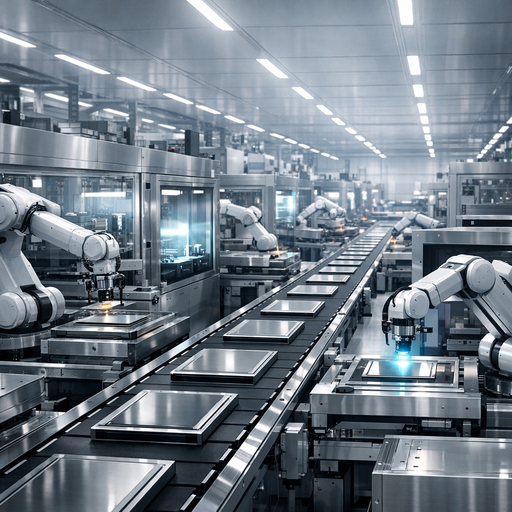

Manufacturing = precision lamination + sintering + atmosphere control

At a high level, SSB manufacturing looks like:

- Make a thin, dense solid electrolyte (via tape casting, sputtering, sintering, or polymer curing).

- Coat high-loading cathodes compatible with that electrolyte.

- Laminate layers with micron-level flatness and uniform pressure.

- Handle sensitive lithium metal without contamination or damage.

- Maintain precise atmospheres (low moisture, controlled oxygen) throughout.

Your mental model: take everything hard about Li-ion manufacturing, add semiconductor-like tolerances, and then ask it to survive mechanical and thermal abuse for a decade.

Where teams get burned (failure modes + anti-patterns)

1. Treating SSBs as a drop-in Li-ion replacement

Anti-pattern:

- EV team assumes they can swap in SSBs at the pack level and “just get more kWh.”

Failure modes:

- Mechanical mismatches: different swelling behavior, different clamping requirements, leading to early cell failures.

- Thermal mismatches: under-designed cooling because “they’re safer,” causing local degradation and impedance rise.

- BMS assumptions: reuse of voltage windows, SoC models, and aging models tuned for liquid cells leads to poor range estimation and premature warranty issues.

2. Underestimating manufacturing yield and capex

Anti-pattern:

- Strategy decks that plug in “$80/kWh by 2030” using best-case cost curves, ignoring yield and rework.

Failure modes:

- Cost blowouts: actual early SSB packs land at 2–3x expected cost.

- Delayed launches: product schedules tied to unrealistic cell delivery timelines.

- Supplier fragility: over-concentration on a single bleeding-edge supplier that can’t hit volume.

3. Ignoring temperature and pressure operating envelopes

Many SSB designs are far more sensitive to:

- Stack pressure: they require a specific pressure range for good interfacial contact but crack or creep if overdone.

- Operating temperature: some solid electrolytes want moderately elevated temperatures for good conductivity; others degrade if too hot.

Failure modes:

- Packs that work beautifully in lab conditions but suffer in:

- Cold climates (poor power at −20°C).

- High-vibration environments (trucks, off-road) where mechanical preload changes.

4. Overfitting infrastructure plans to today’s cell form factors

Example patterns:

- Designing gigafactories (or grid storage containers) that assume cylindrical or prismatic hardcase geometries only.

- Locking in long-lived tooling that’s incompatible with stacked pouch-like SSB designs.

This can make retrofitting for SSBs expensive or impossible without ripping out core infrastructure.

Practical playbook (what to do in the next 7 days)

If you’re a CTO, tech lead, or architect dealing with EVs or grid storage, you can’t build an SSB roadmap in a week. But you can de-risk your future self.

1. Decide if SSBs are strategically relevant to you before 2032

In the next week, answer:

- Are our products:

- EVs with 7–15 year platform lifetimes?

- Grid-scale storage with 10–25 year asset lives?

- High-performance or safety-critical systems (aviation, defense, critical infrastructure)?

If yes, SSBs matter to you. If your horizon is <5 years and mostly low-cost mobility or short-duration storage, they’re mostly noise for now.

2. Create a simple dependency map

Build a one-page document mapping your systems to SSB-sensitive aspects:

-

For EVs:

- Pack architecture (module vs. cell-to-pack).

- Thermal management approach (liquid, refrigerant, air).

- Crash structures around the pack.

- BMS software stack (how hard it is to retune for new chemistries).

-

For grid:

- Container and racking constraints.

- HVAC assumptions.

- Fire suppression and spacing.

- Inverter and power electronics compatibility (voltage windows, current limits).

Mark which parts would need significant redesign to exploit higher energy density, different operating temperatures, or improved safety.

3. Start treating cells like pluggable, not monolithic

You don’t need SSBs in hand to prepare:

- Architect BMS software with chemistry-specific abstraction layers.

- Keep thermal management modular, avoid design choices that hard-code today’s cell envelope.

- For factories, favor flexible tooling where possible (e.g., process lines that can handle a range of cell thicknesses and widths).

This is boring engineering, but it’s exactly what lets you pivot when betas show up.

4. Establish evaluation criteria now

Write down, explicitly, what would convince you to adopt SSBs in a future platform:

- Quantitative thresholds like:

- ≥ X Wh/kg at pack level.

- ≥ Y cycles to Z% capacity at given C-rate and temp.

- Cost/kWh within N% of baseline.

- Verified abuse test results