Solid-State Batteries: Cutting Through the 2025 Hype Wave

Why this matters this week

If you build or buy systems around EV fleets, grid-scale storage, or fast-charging infrastructure, you’re getting hammered by “solid-state is here” headlines again:

- EV OEMs re-committing to “2025–2026” solid-state timelines

- Suppliers announcing “pilot production” and “A-sample cells”

- New grid storage concepts claiming 2–3x energy density and lower fire risk

For people who own reliability SLAs, uptime, and TCO, the questions are narrower and more brutal:

- When can you actually spec a solid-state battery into a product roadmap without betting the company?

- What changes in pack design, thermal management, safety cases, and BMS software?

- Do these cells really reduce fire risk and improve cycle life, or are we just moving the failure modes around?

- What’s the realistic cost curve vs today’s lithium-ion (NMC, LFP) in the 2026–2030 window?

This post is about that: where the commercial solid-state battery reality is today, what still breaks in manufacturing, and what an engineering team should (and should not) do in the next 7 days.

SEO note (integrated naturally): we’ll hit solid-state batteries, EV battery technology, battery manufacturing, grid storage, energy density, and lithium-metal cells along the way.

What’s actually changed (not the press release)

Concrete shifts in the last ~12–18 months, stripped of PR gloss:

-

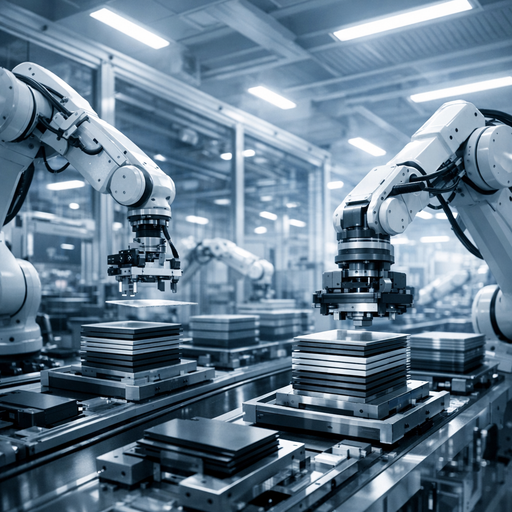

Pilot production that looks like real manufacturing, not lab theater

We now have multiple vendors running:- Tens of MWh/year pilot lines (vs gram-scale coin cells)

- 10–100 Ah large-format prototype cells delivered to OEMs

- Continuous roll-to-roll processes (still low yield) rather than batch lab processes

That matters because the ugly problems—contamination, interface delamination, cracking, and yield collapse—only show up at this scale.

-

Chemistry convergence around a few architectures

Most credible commercial efforts now cluster around:- Sulfur-based or oxide-based solid electrolytes

- Hybrid “semi-solid” or “gel” systems that are not truly dry, but reduce free liquid electrolyte and flammability

- Lithium-metal anode focus to extract density gains (the main reason to do solid-state at all)

This reduces the combinatorial explosion of options; you can actually model risk across 2–3 main chemistries rather than 40 PowerPoint variants.

-

OEM timelines tightening from “someday” to “named programs”

Instead of vague “post-2025” roadmaps, some automakers now talk about:- A specific vehicle platform / trim targeted for solid-state

- Initial use as high-performance, low-volume packs (sports / halo models), not mass-market compact EVs

- First deployments as range-extending or fast-charging variants, not baseline packs

Translation: they’re treating it like a premium, higher-risk technology first, which matches where the manufacturing maturity actually is.

-

Cost expectations getting more sober

Internal models (from fleets and OEMs, not vendors) I’ve seen recently assume:- 1.5–3x current battery $/kWh at launch

- Tapering to parity around 2030 if yields improve and capex amortizes well

- Energy density potentially 1.5–2x vs current LFP, 1.2–1.5x vs current high-nickel NMC

No one serious is planning “cheaper than LFP” in the near term. The pitch is:

- Higher energy density → smaller, lighter packs

- Potentially better cycle life and safety → lower lifetime cost per km / per kWh delivered

-

Regulators and insurers starting to treat solid-state differently

You’re seeing:- Emerging test protocols tailored to solid electrolytes and lithium-metal anodes

- Underwriters quietly asking for more data before signing off on big solid-state deployments, especially for grid storage

Expect extra validation overhead vs standard lithium-ion, at least in early years.

How it works (simple mental model)

You don’t need to be an electrochemist; you need a few mental levers:

-

Same basic sandwich, different middle and anode

Classic EV cell (lithium-ion, liquid/gel electrolyte):- Cathode (e.g., NMC or LFP)

- Porous separator soaked in liquid electrolyte

- Graphite or graphite-silicon anode

Solid-state battery:

- Cathode (similar or slightly tweaked)

- Solid electrolyte layer (ceramic, polymer, or composite)

- Often lithium-metal anode (or anode-less designs where Li plates in-situ)

-

Main theoretical benefits

- Higher energy density: lithium-metal stores more lithium per unit mass than graphite

- Better thermal and safety behavior: less—or no—flammable liquid to leak or vaporize

- Potential for faster charging: if you can control lithium plating and interface stability

-

Where the physics fights you

- Interfaces: solid-solid interfaces between cathode and electrolyte, and electrolyte and Li metal, are hard to keep in intimate contact across thousands of cycles and thermal swings

- Mechanical stress: as lithium moves, volumes change; rigid layers crack, delaminate, or develop voids

- Dendrites don’t magically disappear: lithium can still form dendritic structures in solid electrolytes if current densities, defects, or interfaces are wrong

-

Manufacturing deltas vs today’s lithium-ion

- You still have roll-to-roll coated electrodes, calendering, stacking/winding, and formation steps.

- You add:

- Tight control of solid electrolyte layer thickness and uniformity (tens of microns)

- Often harder calendering and lamination steps to ensure good contact

- Different dry-room constraints (moisture kills some solid electrolytes directly)

- Yield is currently the enemy. Tiny defects = internal shorts or accelerated degradation.

Mental shortcut:

Solid-state isn’t a brand-new category; it’s a more complex variant of the same manufacturing game, but with stricter tolerances and more unforgiving failure modes.

Where teams get burned (failure modes + anti-patterns)

Patterns I’ve seen across OEMs, fleet operators, and grid storage projects evaluating “next-gen” batteries:

-

Assuming lab cycle life translates to field life

- Lab reports: 1,000–2,000+ cycles at mild temperatures, with gentle charging profiles.

- Field reality:

- High C-rate fast charging, thermal gradients, mechanical vibration, pack-level stresses.

- Cell-to-cell variation matters a lot more when your solid electrolyte can crack.

Anti-pattern: extrapolating from 10-cell data to a 10,000-cell pack with the same lifetime.

-

Underestimating integration work at the pack + BMS layer

- New chemistries → new:

- Voltage windows

- Degradation curves

- Temperature dependence

- BMS algorithms (state-of-charge, state-of-health, balancing strategies) built for liquid-electrolyte lithium-ion are not plug-and-play.

Example pattern:

- A team reused their existing fast-charge profile assuming “solid-state is more robust.”

- Result: accelerated interface degradation and uneven plating in early prototypes; cells stayed within voltage limits but SOH fell off a cliff after ~200 cycles.

- New chemistries → new:

-

Ignoring thermal management because “less fire risk”

- Yes, solid-state cells can be safer and less prone to thermal runaway.

- No, that does not mean they like being run hot or cold.

- Many candidate solid electrolytes are more fragile with:

- Repeated thermal cycling

- Localized hotspots at current collectors

Anti-pattern: relaxing pack thermal uniformity targets because “it doesn’t burn.” You trade fire risk for stealthy lifetime loss and capacity fade.

-

Locking product roadmaps to vendor marketing timelines

- “SOP in 2026 with solid-state pack at $80/kWh” shows up in a product roadmap slide.

- Procurement then discovers:

- Vendor yield stuck below 50–60% at scale

- Capex and material costs higher than expected

- First “real” volume slipping to 2028+

The risk isn’t that solid-state never arrives. The risk is anchoring your product launch and unit economics to a specific vendor’s optimistic ramp curve.

-

Treating solid-state as a monolith

- Not all “solid-state” tech is equal:

- Ceramics vs polymers vs hybrids

- Lithium-metal vs silicon-rich vs conventional anodes

- From a systems view, some candidates behave more like “slightly safer lithium-ion” than a step-change in performance.

Example (real-world pattern):

- A grid storage operator evaluated two “solid-state” options:

- Option A: modest energy density gain, strong high-temperature performance, easier manufacturing.

- Option B: huge theoretical energy density, but strict temperature window and unknown long-term stability.

- Early on, internal teams lumped them together as “solid-state = 2x density.” Procurement nearly selected Option B for a use case that didn’t even need the density but did need 20-year life at variable ambient temps. Engineering blocked it just in time.

- Not all “solid-state” tech is equal:

Practical playbook (what to do in the next 7 days)

Assuming you’re a tech lead, architect, or CTO with exposure to EVs, storage, or adjacent systems:

-

Segment your use cases by what actually benefits from solid-state

- Make a short list:

- High energy density critical? (e.g., long-range EVs, aviation, constrained urban storage)

- Fast charge critical?

- Safety / fire-risk reduction critical? (dense urban deployments, underground parking, data centers)

- Also list where existing LFP / NMC is “good enough” given cost and maturity.

- Make a short list:

-

Classify vendor pitches into three maturity buckets

For every “solid-state” vendor in your orbit, demand:- Cell format and capacity (coin, pouch, >10 Ah?)

- Number of cells shipped outside lab

- Current pilot line yield (even a coarse band: <30%, 30–60%, >60%)

- Confirmed customers doing real qualification, not just “MoU”

Then classify:

- R&D only – ignore for product planning

- Pilot with real OEM quals – candidate for limited-scope