Solid-State Batteries: What’s Real in 2025 and What Isn’t

Why this matters this week

If you work on EVs, charging infrastructure, energy storage, or grid planning, solid-state batteries stop being abstract R&D once they hit pilot manufacturing at scale. That is happening now.

In the last 6–9 months:

- Multiple OEMs have locked in concrete (if small) production timelines for solid-state EV packs.

- At least three serious players have moved from coin/pouch “lab cells” to fully automated pilot lines.

- Grid storage folks are quietly running the numbers on when higher energy density and better safety could change siting, insurance, and BOS (balance-of-system) costs.

The question isn’t “are solid-state batteries the future?” It’s:

- When will they matter for your next-gen platform (EV or stationary)?

- What constraints will their manufacturing and supply chain add?

- How do you avoid designing yourself into a dead end (wrong form factor, wrong chemistry, wrong charge profile)?

You don’t need to become a battery chemist. But you do need a realistic mental model of:

- Where solid-state batteries are truly better than today’s lithium-ion.

- Where they are worse or uncertain.

- What a credible 2027–2032 adoption curve looks like for your systems.

What’s actually changed (not the press release)

The marketing headlines say: “2x energy density, 10-minute charging, absolutely safe, commercial by 2025.” That’s not reality. Here’s what has actually changed in 2024–2025.

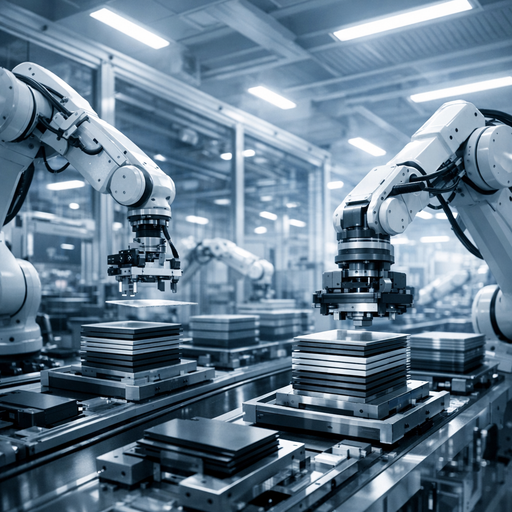

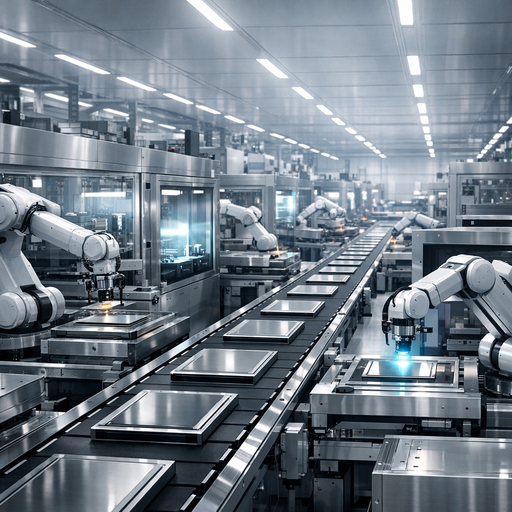

1. Pilot manufacturing is real, not just lab-scale

Several vendors have:

- Fully automated pilot lines producing tens to low hundreds of MWh/year.

- Yields that are no longer a rounding error—think 60–80% instead of sub-20%.

- Pack-level validation programs with major automakers and at least one grid-scale integrator.

This is a big step up from pretty pictures of coin cells.

Implication: You can now get real data (cycle life, safety, fast charge behavior, failure modes) on semi-production cells, not extrapolated lab curves.

2. Chemistries are narrowing to a few plausible winners

In practice, the “solid-state” conversation in commercial roadmaps is converging on:

- Sulfide-based solid electrolytes (high ionic conductivity, more sensitive to moisture, manufacturing complexity).

- Oxide-based (e.g., garnet-type) electrolytes (more stable, difficult interfaces, higher processing temperatures).

- Polymer-hybrid / semi-solid approaches (less dramatic step change, easier manufacturability, safer and incremental).

Metal anode (Li metal) remains the key lever for energy density, but:

- Many near-term “solid-state” packs are actually graphite or silicon-graphite anodes with solid or semi-solid electrolytes.

- Full Li-metal anodes with consistent cycle life >800–1000 cycles at EV-relevant C-rates are still not widely demonstrated at scale.

Implication: For 2027-ish EVs, expect incremental improvements first (better safety, modest range increase), not magic 800-mile cars.

3. Safety and abuse tolerance data is maturing

We’re now seeing:

- Nail penetration and crush tests where packs don’t go into thermal runaway.

- Higher tolerance to overcharge and external short events, especially for sulfide and oxide systems.

- Lower reliance on heavy mechanical containment and fire mitigation structures.

Implication: At the pack and system level, you may claw back volume and weight from safety overhead, even if cell-level Wh/kg isn’t fully doubled yet.

4. Cost curves are better understood (but still not great)

- Near-term (through ~2030), solid-state cells look more expensive per kWh than state-of-the-art NMC or LFP, due to:

- More complex processing (dry room requirements, sintering, vacuum, high-precision stacking).

- Lower yields and higher capital intensity.

- Long-term projections (post-2030) rely heavily on:

- Scaling specific manufacturing methods (e.g., roll-to-roll solid electrolyte deposition).

- Achieving commodity-like supply of solid electrolyte materials.

Implication: For the next product cycle or two, solid-state is a premium option, not a cost-down play—unless safety/pack density saves you enough downstream to offset cell cost.

How it works (simple mental model)

Strip away the jargon. A solid-state battery is still:

- An anode (ideally lithium metal or high-silicon composite).

- A cathode (often high-nickel NMC or similar; some exploring high-voltage or high-loading cathodes).

- An electrolyte (now a solid, not a flammable liquid).

- Interfaces between the solid electrolyte and the electrodes.

Two main differences vs conventional lithium-ion:

- The electrolyte is solid.

- It moves lithium ions but should not move electrons.

- Ideally non-flammable, less prone to leakage and thermal runaway.

- The interface becomes the key problem.

- Ions cross from electrode → solid electrolyte through a boundary layer.

- Mismatch in mechanical properties (brittle electrolyte vs expanding anode) causes:

- Cracks

- Voids

- Dendrite channels

A reasonable mental model:

- Think of a solid-state cell as a high-performance, high-strain multi-layer ceramic stack.

- Your failure modes are:

- Mechanical (cracks, delamination).

- Electrochemical (instability at high voltages, side reactions, interface resistance growth).

- Manufacturing (defects that become initiation sites for dendrites.)

This is why:

- Fast charging remains hard—current must traverse fragile interfaces without forming local hot spots.

- Cycle life is extremely sensitive to current density and temperature control.

Where teams get burned (failure modes + anti-patterns)

From both public data and private anecdotes, a few patterns repeat.

1. Over-committing product timelines to marketing claims

Pattern:

An EV team adopts a vendor roadmap:

- “Sample cells this year”

- “Automotive-qualified packs in 2027”

- “Mass production 2028”

They design an entire platform around 30–50% higher pack energy density. What actually happens:

- Cell format changes (e.g., pouch → prismatic) mid-development.

- Qualification cycles slip by 18–24 months.

- Early packs don’t meet cycle life targets at real-world charge patterns (e.g., frequent DC fast charging).

Result: rushed redesign to fit conventional Li-ion modules, compromised vehicle packaging, write-downs on tooling.

Anti-pattern: Treating solid-state like a drop-in upgrade with fixed specs.

2. Ignoring thermal and mechanical management differences

Pattern:

A stationary storage team assumes better safety = simpler thermal/mechanical design:

- Reduces mechanical compression systems (critical for interface stability).

- Under-sizes thermal management because cells run “cooler”.

Result:

- Uneven mechanical pressure leads to microcracks in solid electrolyte.

- Localized hot spots at high C-rates accelerate interface degradation.

- Premature capacity fade and unexpected impedance growth; some modules fail early.

Anti-pattern: Assuming standard Li-ion pack design principles apply 1:1.

3. Underestimating manufacturing and QA constraints

Pattern:

A startup builds a business model on solid-state packs available at automotive-scale yields by 2028:

- Models cost on theoretical material inputs and capex only.

- Does not account for:

- Yield drag from solid electrolyte defects.

- Additional inline inspection and metrology.

- Tighter dry-room and cleanliness standards.

Result: BOM and cell pricing assumptions off by 30–50%; entire product P&L misaligned.

Anti-pattern: Using material-level cost estimates without manufacturing reality.

4. Misaligned use cases: chasing range instead of safety or form factor

Pattern:

An OEM treats solid-state batteries solely as a “650+ mile range” feature.

- Designs a larger, heavier vehicle to “use all that energy.”

- Ignores potential to shrink pack footprint, lower center of gravity, or reduce safety structures.

Result: Marginal real-world differentiation (drivers rarely use full range), while paying premium for cells.

Anti-pattern: Not tying the technology to concrete system-level metrics like pack volume reduction, safety zoning, or charging throughput.

Practical playbook (what to do in the next 7 days)

You can’t fix chemistry in a week, but you can de-risk your roadmap.

1. Write down your “solid-state hypothesis” in numbers

For your domain (EV, grid, or industrial), specify:

- Target pack-level gains you care about:

- +X% Wh/kg and Wh/L

- Y% reduction in pack safety mass/volume

- Z% improvement in fast-charge time (e.g., 10–80% in ≤15 min)

- Required cycle/calendar life

- Acceptable cell cost premium (%) vs today’s Li-ion if requirements are met.

If you can’t quantify this, you’re not ready to commit.

2. Separate “chemistry-agnostic” vs “chemistry-dependent” design choices

In your architecture/decomposition docs, label components:

- Chemistry-agnostic:

- High-level BMS architecture (modular, updatable).

- Pack segmentation, safety zoning, and isolation.

- Thermal system scalability.

- Chemistry-dependent:

- Compression mechanisms for cells.

- Voltage windows and charge profiles.

- Connector layout tied to specific form factors.

Aim to:

- Keep chemistry-dependent decisions as late-binding as possible.

- Design interfaces (mechanical, electrical, software) that can support both advanced Li-ion and emerging solid-state battery packs.

3. Schedule a hard-nosed vendor conversation

If you’re considering solid-state suppliers, in the next 7 days:

- Ask for:

- Current pilot line yield numbers (even as ranges).

- Tested cycle life at:

- Realistic C-rates

- Realistic temperature ranges

- Realistic fast-charge patterns

- Actual pack-level safety and abuse test results.

- Ask what they don’t know yet:

- Specific failure modes they’re still characterizing.

- Long-term calendar life data gaps (e.g., >10 years).

Red flag: Any vendor that won’t discuss yield, cycle test conditions, or specific failure learnings.

4. Run a quick risk-adjusted roadmap scenario

For your next major platform or product generation, sketch three scenarios:

- No solid-state: You stay with advanced Li-ion (e.g., NMC, LFP, LMFP).

- Hybrid strategy: Design to support both Li-ion and solid-state within same chassis/plant.

- Full commit: Design only for solid-state assumptions (energy density, form factor,