Stop Treating AWS Serverless as “Free Glue”: A Practical Guide to Cost-Aware, Observable Platforms

Why this matters this week

AWS bills keep surprising teams that thought “serverless = cheap,” and platform groups are being asked two questions at the same time:

- “Can we go faster with serverless and managed services?”

- “Why is our bill unreadable, our cold-starts brutal, and our incident response dependent on that one staff engineer who speaks CloudWatch?”

Under pressure, many organizations are converging on a similar pattern:

- Event-driven serverless (Lambda, EventBridge, SQS, Step Functions)

- A thin “platform” layer that standardizes networking, observability, and IAM

- A bunch of micro-stacks that product teams own

The catch: the failure modes of this pattern are subtle and expensive:

- Concurrency explosions and throttling storms

- Hidden data transfer and cross-service API costs

- Un-deployable spaghetti of CloudFormation stacks

- No common observability language across teams

This post focuses on cloud engineering on AWS with three lenses:

- Cost optimisation that doesn’t sabotage reliability

- Serverless patterns that scale without surprise

- Platform engineering that creates guardrails instead of red tape

If you’re a tech lead or CTO, the next 12 months of your cloud strategy are mostly about getting these mechanics right, not chasing the next acronym.

What’s actually changed (not the press release)

Several concrete shifts in AWS serverless and platform tooling in the last 12–18 months materially change how you should design:

-

Lambda cost & scaling behavior is “good enough” to be your default for a lot of workloads.

- Graviton, per-ms billing, and better provisioned concurrency controls mean:

- It’s easier to keep latency predictable.

- The cost gap vs. containers is smaller than many 2020-era calculators show.

- But: at sustained high throughput (>100–200 req/s steady per function), Fargate or ECS on EC2 is often cheaper.

- Graviton, per-ms billing, and better provisioned concurrency controls mean:

-

EventBridge and SQS have become the de facto backbone for decoupled systems.

- EventBridge now reasonably supports:

- Complex routing

- Schema registry

- Cross-account event buses

- SQS remains the “boring reliable queue,” but:

- FIFO and high-throughput modes are shaping real-time and ordering-sensitive patterns.

- This gives teams a standard way to build event-driven architecture without building their own pub/sub.

- EventBridge now reasonably supports:

-

Observability on AWS is less awful, but still not turnkey.

- CloudWatch + X-Ray + CloudWatch RUM / Evidently + Lambda Telemetry APIs:

- You can get traces and metrics without huge vendor spend.

- The problem has shifted:

- From “we can’t get data”

- To “we have more data than any human can navigate during an incident.”

- This is where platform engineering and standardization matter.

- CloudWatch + X-Ray + CloudWatch RUM / Evidently + Lambda Telemetry APIs:

-

Platform-as-a-product is becoming normal inside mid-sized orgs.

- Internal platform teams are:

- Shipping golden paths with CDK/Terraform modules

- Standardizing “how to build a service” (API, queue, lambda, metrics, alarms)

- Managing shared concerns: network, IAM, logging, SSO, cost allocation

- The decisions those teams make about AWS serverless patterns now have org-wide cost and reliability impact.

- Internal platform teams are:

None of these are futuristic. They’re just… mature enough that ignoring them is now a risk.

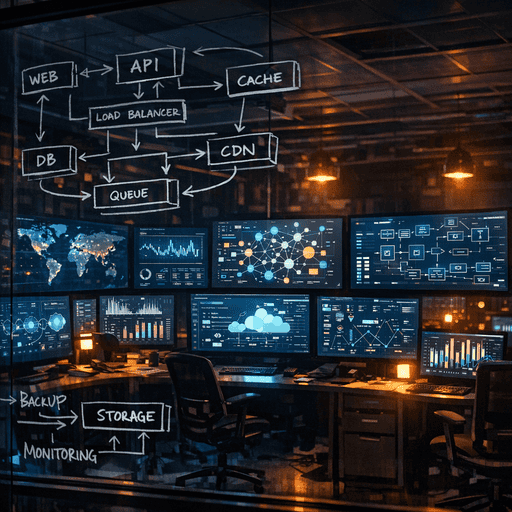

How it works (simple mental model)

Use this mental model to reason about AWS serverless platforms:

1. Four “planes” of your architecture

Think of your system as four planes:

- Execution plane – where code runs

- Lambda, Fargate, ECS on EC2

- Data plane – where state lives and moves

- DynamoDB, RDS, S3, SQS, EventBridge, Kinesis

- Control plane – how you deploy, configure, and authorize

- CloudFormation/CDK/Terraform, IAM, AWS Organizations, AWS Config

- Observation plane – how you see what’s happening

- CloudWatch, X-Ray, OpenTelemetry pipelines, cost explorer/cur

“Serverless” mainly shifts responsibilities across these planes:

- You rent the execution plane and much of the control plane.

- You still own the data plane design and observation plane discipline.

2. Cost vs. reliability as sliders, not switches

For each workload, you can roughly place it on two axes:

- Volatility of traffic (spiky vs. steady)

- Tolerance for latency / cold-start / jitter (strict vs. loose)

Then you choose:

- Highly spiky + loose latency → Lambda + SQS / EventBridge

- Steady + predictable latency needed → Fargate or ECS on EC2

- Hybrid (day steady, night spiky) → containers as baseline, Lambda for burst or background jobs

This avoids the “Lambda everywhere” or “Kubernetes everywhere” religion.

3. Ownership boundaries, not microservice dogma

Instead of counting microservices, define:

- Service = something that a team can own end-to-end, including on-call and cost.

- Within that, you might have:

- A small bundle of Lambdas, queues, and tables

- Or a containerized API and batch worker

You’re optimizing for operational ownership, not diagrams.

Where teams get burned (failure modes + anti-patterns)

Failure mode 1: Lambda concurrency shock

Pattern:

- A “simple” Lambda API is added behind API Gateway.

- Traffic spikes after a feature launch.

- Lambdas scale out quickly, but:

- Downstream RDS or third-party APIs are overwhelmed.

- Throttles trigger retries, amplifying the load.

- Costs and latency jump simultaneously.

What’s missing:

- Concurrency controls (per-function reserved concurrency)

- Backpressure and queuing (SQS or Kinesis in front)

- Explicit rate limits to third-party APIs

Failure mode 2: Event spaghetti with no schema discipline

Pattern:

- Teams love EventBridge and SQS.

- Every team publishes events with slightly different shapes, naming, and contracts.

- Six months in, no one knows:

- Who consumes what

- Whether a field can be changed

- Which events are critical for billing, compliance, or SLAs

Consequences:

- Fear of change → slowed delivery

- Silent failures in downstream consumers

- Hard to reason about incident blast radius

Failure mode 3: Observability as a per-team snowflake

Pattern:

- Each team picks their own logging format, tracing library, and metric conventions.

- Some use X-Ray, some use vendor A, others vendor B, some nothing.

- During incidents:

- SREs and on-call engineers spend precious minutes switching tools and mental models.

- Cross-service traces are partial or non-existent.

Result:

- MTTR is longer than it should be.

- You pay for lots of telemetry but can’t reliably answer “what broke where?”

Failure mode 4: Platform team as ticket factory, not product

Pattern:

- Platform team owns:

- IAM roles, shared VPCs, base images, CI/CD templates

- No clear golden paths or self-service:

- Product teams open tickets for everything.

- Workaround culture grows (copy-paste of old stacks, manual changes).

- Platform backlog is a mixture of:

- “Fix prod now” tickets

- “We should build a proper platform” aspirations

Outcome:

- Frustrated dev teams

- Opaque cost drivers

- Shadow infrastructure and drift from best practices

Practical playbook (what to do in the next 7 days)

This assumes you already run on AWS. Adapt scale to your org size.

1. Inventory your “serverless estate” (half day)

Pull a minimal map:

- List:

- All Lambda functions

- SQS queues & EventBridge buses

- Step Functions state machines

- For each, capture:

- Owning team

- Primary downstream data stores (RDS, DynamoDB, S3)

- Whether it’s production-critical

Outcome: a simple table you can reason about for cost and reliability.

2. Put hard limits where you have none (1 day)

For critical Lambdas:

- Set Reserved Concurrency:

- Start with a number that protects downstreams but can handle expected peak.

- Example: if RDS can handle ~200 TPS safely, don’t let a single Lambda scale to 1000 concurrent.

- For external APIs (payments, CRM, etc.):

- Introduce SQS in front of the Lambda if calls are bursty.

- Add dead-letter queues to capture failures without hammering the vendor.

Measure:

- Error rates and throttles before/after

- Queue depth patterns during peak

3. Standardize minimal observability (2–3 days with platform + 1–2 teams)

Define a “baseline observability contract”:

- For all production workloads:

- Structured logs: JSON with at least

request_id,service_name,environment,severity,tenant(if multi-tenant). - Three standard metrics:

latency_ms(p50/p95)error_ratethroughput(requests or events per second)

- Tracing:

- Choose either native X-Ray or a single OpenTelemetry approach.

- Mandate propagating correlation IDs through async hops (SQS message attributes, EventBridge detail).

- Structured logs: JSON with at least

Platform team:

- Ship language-specific logging + tracing libraries (or wrappers) that:

- Automatically inject these fields

- Integrate with CloudWatch Logs and X-Ray/OTel exporter

- Provide one dashboard template per service:

- Latency, error, and saturation metrics across Lambdas and queues

Goal: any engineer can debug 80% of issues without reading a 50-page wiki.

4. Create a simple event contract playbook (1 day to draft, ongoing to adopt)

Decide:

- Where events are first-class contracts:

- e.g., Orders, Payments, UserCreated, SubscriptionChanged

- For those:

- Define ownership: which team owns the schema.

- Define versioning rules:

- Backwards-compatible changes OK (additive).

- Breaking changes require new event types or version fields.

- Document consumers and criticality.

Start with the critical flows:

- Billing, compliance-sensitive events, order lifecycle

You don’t need a full schema registry day 1. A Markdown file or internal doc with 10–20 event types is a big step.

5. Baseline cost and identify 2–3 high-leverage savings (1–2 days)

Work with FinOps / platform:

- Pull per-service cost from