The Hidden Cost of “Serverless Sprawl” on AWS (and How to Get Ahead of It)

Why this matters this week

AWS serverless used to be the “cheap by default” choice. For many teams, it no longer is.

Over the last 12–18 months, three trends have converged:

- Lambdas and Step Functions are now orchestrating critical, always-on production flows, not just “glue code.”

- Teams have layered on more managed services (API Gateway, EventBridge, DynamoDB, SQS, SNS, Kinesis, Aurora Serverless, AppSync) without a coherent platform engineering strategy.

- Finance and security are finally looking closely at cloud bills and incident reports.

The result: a growing number of organizations discover that their “modern serverless architecture” is:

- More expensive than an equivalent container-based design

- Harder to reason about under failure

- Poorly observable (especially in cross-service workflows)

- Owned by no one in particular (infra is “everybody’s problem”)

This week’s post focuses on putting structure back into AWS cloud engineering before your architecture calcifies into an expensive, unreliable maze.

What’s actually changed (not the press release)

Nothing “broke”; AWS has just done what AWS does: shipped more building blocks with overlapping use cases. Your environment is probably more complex than you think.

Concrete changes in the last couple of years that matter for cost, reliability, and observability:

-

More always-on workloads on “serverless”

- Long-running event-driven workloads (stream processing, real-time enrichment, API backends) now live on Lambda, Fargate, and Aurora Serverless.

- These don’t benefit as much from “scale-to-zero” economics. If your Lambda is effectively hot 24/7, you’re closer to running an over-priced microservice.

-

Increased use of orchestration services

- Step Functions, EventBridge, and SQS are everywhere.

- Each improves local concerns (retries, decoupling, fan-out), but globally they form complex chains with emergent behavior under partial failure.

-

Cost visibility improved—but only slightly

- AWS Cost Explorer and tags are better, but:

- Most teams don’t have consistent tagging enforced by policy.

- Unit economics (cost per event, per API call, per tenant) are rarely defined.

- AWS Cost Explorer and tags are better, but:

-

Security baselines got stricter

- CIS benchmarks, zero trust pressure, and internal audits now expect:

- Least-privilege IAM for each function/microservice

- Encryption, restricted egress, and proper secret handling

- Retrofitting these onto an organically grown serverless landscape is painful.

- CIS benchmarks, zero trust pressure, and internal audits now expect:

-

Platform engineering is expected, but under-resourced

- Many orgs have “platform teams” in name only—2–3 people trying to standardize AWS usage across dozens of squads and hundreds of Lambdas.

- Without clear platform contracts, each team re-discovers patterns: logging, retries, idempotency, DLQ handling, etc.

Net: AWS hasn’t become worse, but the naive “just use managed services and we’ll be fine” story is no longer true for teams at scale.

How it works (simple mental model)

A practical mental model for AWS cloud engineering in 2025:

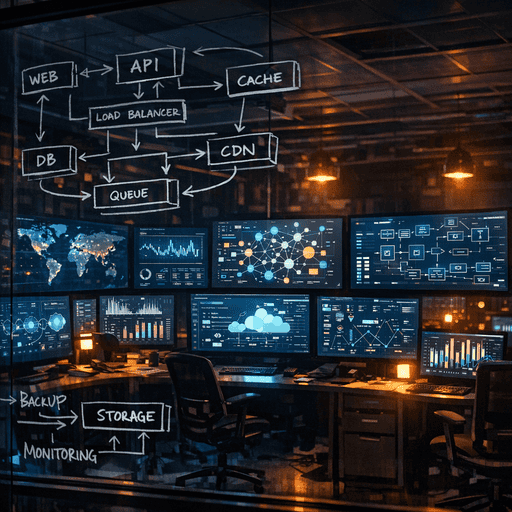

Treat AWS as three distinct layers: execution, integration, and governance. Design each explicitly.

1. Execution layer (where code runs)

This is Lambda, Fargate, ECS, EKS, EC2.

Key questions:

– For each workload, is it:

– Burst + unpredictable → Lambda often wins on both cost and ops.

– Steady + high-throughput → Containers or provisioned concurrency usually win.

– What is your smallest supported unit?

– Decide: “For new HTTP APIs, default to Fargate/ECS unless latency or burst pattern justifies Lambda.”

Mental shortcut:

– If average concurrency > ~10 and traffic pattern is stable: model Lambda vs Fargate cost. Don’t assume serverless is cheaper.

– If you need fine-grained language/runtime control, complex networking, or sidecars: containers.

2. Integration layer (how components talk)

This is API Gateway, ALB, EventBridge, SNS/SQS, Kinesis, DynamoDB streams, Step Functions.

Pick two primary patterns as defaults:

- Sync over HTTP: API Gateway or ALB for request–response APIs.

- Async events: EventBridge or SQS/SNS for decoupling services.

Everything else (Kinesis, DynamoDB Streams, etc.) should be an explicit exception with a clear reason (throughput, ordering, replay).

Mental shortcut:

– Prefer EventBridge for domain events (loose coupling) and SQS for work queues (back-pressure, explicit workers).

– Use Step Functions only when you truly need workflow semantics (human approvals, long-running processes, complex compensations).

3. Governance layer (how you keep it sane)

This is where cost optimisation, security, and observability actually live:

- Scaffolding: templates or internal CLIs that create new services with:

- Standard logging

- Tracing

- Metrics

- IAM roles

- Alarms

- Guardrails: SCPs, Config rules, CI policies that:

- Enforce tagging

- Block public buckets

- Disallow wild-card IAM in production

- Visibility:

- Standard dashboards per service (latency, error rate, utilization, cost)

- Central error tracking and distributed tracing

If this layer is missing, your AWS account becomes a junk drawer of “one-off solutions.”

Where teams get burned (failure modes + anti-patterns)

1. The “free scaling” illusion

Pattern:

– “We never need to think about capacity again; Lambda scales for us.”

Failure mode:

– Sudden cost spikes when a batched or buggy client hammers an endpoint.

– Downstream systems (databases, third-party APIs) become the bottleneck.

– You discover throttling or connection limits only in production.

Mitigation:

– Concurrency limits on Lambdas.

– Load-shedding logic and back-pressure (SQS redrive, DLQs).

– Rate-limiting at API Gateway or a front door like CloudFront.

2. Step Functions as a distributed monolith

Pattern:

– Complex Step Functions workflows with 20–50 steps, cross-region calls, and embedded business logic.

Failure mode:

– Hard to test end-to-end.

– State machine changes risk breaking multiple domains.

– Debugging failures requires deep knowledge of the whole orchestration.

Mitigation:

– Treat Step Functions as orchestration for one bounded context.

– Keep business logic in code, not in the state machine.

– Favor smaller workflows composed via events, not one giant “super-flow.”

3. Unbounded event-driven architectures

Pattern:

– “When X happens, publish an event. Everyone can subscribe!”

– Over time, 10–20 services subscribe to a core domain’s events.

Failure mode:

– You can’t safely change the event schema.

– A single bad subscriber can amplify issues (e.g., retries across many consumers).

– Hard to understand impact of a change (“who listens to this event?”).

Mitigation:

– Version your events deliberately.

– Maintain an event catalog (even a simple YAML/markdown registry).

– Enforce consumer contracts: dead-letter queues, timeouts, explicit error handling.

4. Observability as an afterthought

Pattern:

– Logging with print() and ad-hoc CloudWatch Logs browsing.

– Multiple tracing libraries, if any.

Failure mode:

– Incident response starts with, “Where even is this request flowing?”

– Cost spikes are detected late because nobody tracks cost per transaction.

Mitigation:

– Adopt a single logging/tracing standard (OpenTelemetry or vendor-specific, but consistent).

– For each critical workflow, define:

– A trace ID that flows through all components.

– A small set of golden signals: latency, error rate, saturation, cost-per-unit.

5. “Everything is serverless” religion

Pattern:

– Policy that new workloads must be built with Lambda + API Gateway + DynamoDB, regardless of fit.

Failure mode:

– Long-running jobs jammed into Lambda with timeouts and stepwise hacks.

– Overuse of DynamoDB where relational queries would have been simpler and cheaper.

– Developers build convoluted patterns to mimic features containers or RDS would natively provide.

Mitigation:

– Make technology choices contextual, not ideological.

– Publish a short decision matrix:

– “Use Lambda when …”

– “Use Fargate/ECS when …”

– “Use RDS vs DynamoDB when …”

Practical playbook (what to do in the next 7 days)

The point is not to redesign your architecture in a week. It’s to create a baseline of control.

Day 1–2: Get visibility

-

Tagging audit

- Identify top 20 costliest AWS resources by service (Lambda, API Gateway, DynamoDB, Fargate, etc.).

- Check if they have:

env,service,team,cost-centertags.

- Outcome: a simple spreadsheet with “owned vs orphaned” workloads.

-

Cost-per-unit sketch

- Pick one or two core business flows (e.g., “process order”, “ingest event”).

- Approximate:

- Invocations per day

- Total daily cost for services in that flow

- Derive an approximate cost per transaction. You don’t need perfect numbers, just order of magnitude.

Day 3: Map one critical workflow

Create a diagram for one important end-to-end flow:

- Start at the entrypoint (API Gateway, S3 event, Kinesis, etc.).

- Map every hop: Lambda → SQS → Lambda → DynamoDB → Step Function → external API.

- Annotate each with:

- Latency expectations

- Error handling (retries, DLQ, circuit breaker?)

- Cost hotspots (e.g., API Gateway with high request volume)

Deliverable: a single page diagram that ops and devs can review together.

Day 4: Define your default patterns

In a short doc (1–2 pages), define your defaults:

- Execution:

- When to use Lambda vs Fargate/ECS.

- Default memory/time settings, concurrency limits.

- Integration:

- Default for async (SQS vs EventBridge).

- Default for sync (API Gateway vs ALB).

- Observability:

- Required metrics and logs for any new service.

- Required alarms (error rate, latency, throttles).

Make clear that deviations are allowed but must be justified.

Day 5: Add one guardrail and one template

- Guardrail

- Example: A CI check that fails builds if:

- Lambda has no

service/teamtags.

–

- Lambda has no

- Example: A CI check that fails builds if: