Your Lambda Bill Is Lying To You: Serverless Cost & Reliability Patterns That Actually Hold Up

Why this matters this week

AWS serverless (Lambda, API Gateway, EventBridge, Step Functions, DynamoDB, SQS) has reached the “legacy” phase in many orgs:

- The first wave of functions are now 3–6 years old.

- Bills are weirdly high despite “you only pay for what you use.”

- Incidents are increasingly about glue code between services, not the business logic.

- Platform teams are being asked to “standardise serverless” or “move to serverless for cost.”

The marketing line is still: “Serverless is cheaper, more scalable, and you don’t manage servers.”

In production, the real questions are:

- When is serverless actually cheaper than containers on ECS/EKS?

- How do we make it observable and debuggable enough that on-call doesn’t hate it?

- How do we stop every team hand-rolling their own half-baked platform?

This post is about cloud engineering on AWS with that lens: cost, reliability, and platform patterns that survive contact with real traffic.

SEO keywords woven in: AWS serverless, AWS Lambda cost optimization, AWS observability, cloud cost management, platform engineering on AWS, serverless reliability.

What’s actually changed (not the press release)

The last 12–18 months on AWS serverless have materially changed the trade-offs for cloud engineering, mostly in ways that aren’t obvious from the console.

Key shifts:

-

Lambda cost profile has become more “normal”

- Lambda Power Tuning and the new pricing with more granular memory/CPU options make it easier to right-size.

- Provisioned Concurrency and SnapStart reduce cold starts but add fixed cost. Many teams quietly turned these on “for performance” and never revisited them.

- Result: Lambda is no longer “always cheaper at low volume.” You can accidentally lock in a floor cost that rivals a small ECS Fargate cluster.

-

EventBridge + Step Functions are now default glue

- Many workloads that used to be custom queues and cron Lambdas moved to EventBridge for fan-out and scheduling, and Step Functions for orchestration.

- This improves reliability and traceability, but multiplies billable events. It also changes your failure modes from “Lambda timeout” to “infinite retries, dead-letter queues, and orphaned executions.”

-

Observability is more possible, but still not automatic

- CloudWatch Logs Insights is powerful but underused.

- Distributed tracing with X-Ray is decent if you’re disciplined with headers and sampling.

- Native metrics for things like async Lambda failures, DLQs, and throttling exist but aren’t wired into dashboards by default.

- Net effect: the teams that invest a few days into observability are fine; the rest fly blind until an incident.

-

Platform engineering is central, not optional

- Terraform/CDK patterns, IAM baselines, and standardised logging/tracing middleware are now the main leverage points.

- Individual teams “just wiring things together” without a platform opinion get:

- Dozens of inconsistent runtimes and timeouts

- IAM sprawl

- Cost allocation that’s basically impossible to untangle

The big change: serverless on AWS has matured from “experiments” to “platform problem.” The tactical knobs (memory, timeouts, retries) matter, but the real wins are in standardisation and clear patterns.

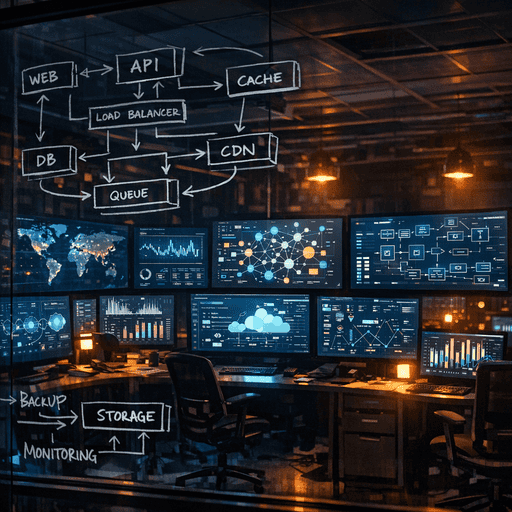

How it works (simple mental model)

A useful mental model for AWS serverless cost and reliability:

You’re not paying for functions, you’re paying for edges between services.

And you debug by following those edges.

Break it down:

-

Nodes: stateless units of work

- Lambda functions

- Step Functions states

- Fargate tasks (when you do hybrid)

- DynamoDB operations (from a cost perspective)

Each node has:

- A performance envelope (memory, CPU, timeout)

- A reliability envelope (retries, DLQs)

- A cost envelope (duration * memory + per-request)

-

Edges: how work moves around

- API Gateway → Lambda

- EventBridge → Lambda

- Lambda → DynamoDB / SQS / SNS / external API

- Step Functions → Lambda → SQS, etc.

Each edge has:

- A fan-out factor (how many downstream calls per event)

- A delivery guarantee (at-least-once, exactly-once-ish, best-effort)

- A visibility level (is it logged, traced, metrically visible?)

-

Cost and reliability mostly live on edges, not nodes

- Cost explosion often comes from:

- Too many small functions with chatty edges (lots of API calls, lots of logs, lots of events).

- Orchestration in Lambdas instead of Step Functions, leading to retries that re-run entire workflows.

- Reliability issues often come from:

- Misconfigured retries (thundering herds on downstream systems).

- Invisible failure queues (DLQs never monitored).

- Partial failures across multiple edges (one Lambda in a chain silently fails).

- Cost explosion often comes from:

-

Platform engineering is about pre-configuring nodes and edges

- Default timeouts, memory settings, and concurrency.

- Standard ways to do idempotency, retries, DLQs.

- Shared libraries/middleware for logging, tracing, and metrics.

- Infrastructure-as-code modules to make the “right” pattern the easiest pattern.

If you think in “edges first” you naturally ask:

- How many round-trips are we making?

- What happens when this dependency is slow or down?

- How do we see this edge in metrics and traces?

- Is this orchestration (Step Functions) or transformation (Lambda) work?

Where teams get burned (failure modes + anti-patterns)

1. “Every micro-step gets its own Lambda”

Pattern: A single business operation (e.g., “place order”) becomes 10–20 tiny Lambdas chained via EventBridge or Step Functions.

Issues:

– High cognitive load: no one can debug end-to-end without 3 dashboards and reading code.

– Cost bloat: each Lambda has startup overhead and CloudWatch log cost; often the whole flow could run comfortably within one function or one container.

– Latency: each hop adds API overhead and sometimes cold starts.

Healthy counter-pattern:

– Group tightly coupled steps with shared error handling into a single Lambda or container.

– Use Step Functions for coarse-grained orchestration, not every if/else.

2. Hidden fixed costs: Provisioned Concurrency and SnapStart

Pattern: “We turned on Provisioned Concurrency to fix cold starts” and never revisited.

Issues:

– Perpetual fixed cost that may exceed container-based alternatives at moderate traffic.

– Often applied to many small Lambdas instead of a few critical user-facing ones.

– Low utilisation outside peak hours.

Healthy counter-pattern:

– Restrict Provisioned Concurrency / SnapStart to:

– Latency-sensitive APIs with real user impact.

– High and consistent traffic functions.

– Review monthly:

– Percent of invocations hitting provisioned capacity.

– Compare monthly Lambda cost vs an equivalent ECS/Fargate service.

3. No global view of retries and DLQs

Pattern: Async Lambdas, SQS triggers, EventBridge rules—each with its own retry and DLQ semantics—configured ad-hoc.

Issues:

– Silent data loss when DLQs are misconfigured or unmonitored.

– Retry storms hitting downstream systems during partial outages.

– On-call confusion: “Which queue actually has the failed events?”

Healthy counter-pattern:

– Platform team provides:

– Standard retry policies by event type (idempotent vs non-idempotent).

– One central DLQ per domain with mandatory alarms.

– A standard dead-letter message format with correlation IDs and metadata.

4. Observability as an afterthought

Pattern: Each team logs however they like, if at all. No standard trace IDs. No central dashboards.

Issues:

– Debugging a 500 in a mobile API takes 2–3 people spelunking different logs.

– Lambda timeouts vs downstream latency are hard to distinguish.

– Cost anomalies detected only by finance, not engineering.

Healthy counter-pattern:

– Shared library/middleware that:

– Injects/propagates a correlation ID and distributed trace context (HTTP headers, SQS message attributes, etc.).

– Logs in JSON with a consistent schema.

– Emits basic metrics (latency, error rate) per function and key edge.

– A baseline dashboard for:

– Top N Lambdas by cost.

– Error rates and throttling for all event sources.

– DLQ depth and age of oldest message.

5. Unbounded fan-out

Pattern: “We’ll just publish an event and let consumers subscribe” with no hard caps.

Issues:

– A single high-volume event (e.g., “order updated”) fans out to many subscriber Lambdas, some of which call external APIs → cost and rate-limit pain.

– Difficulty reasoning about the impact of a schema change or outage.

Healthy counter-pattern:

– Domain event contracts: document expected volume and behaviour.

– Use:

– SQS between EventBridge and high-cost consumers.

– Rate limiting and backpressure for external API consumers.

– Per-consumer cost dashboards: some subscriptions may be too expensive for the value they add.

Practical playbook (what to do in the next 7 days)

Assume you’re a tech lead or platform engineer with existing AWS serverless usage.

Day 1–2: Inventory and basic telemetry

-

Map your top 20most expensive Lambdas

- Use AWS Cost Explorer or internal tagging to find:

- Cost per function (Lambda + logs + related API Gateway/Step Functions).

- For each, record:

- Runtime, memory, avg duration, concurrency, trigger type.

- Use AWS Cost Explorer or internal tagging to find:

-

Baseline critical event edges

- For each core business flow (e.g., signup, checkout, ETL job):

- List the sequence: API Gateway → Lambda → EventBridge → Lambda → SQS → Lambda → DynamoDB, etc.

- Identify:

- Where retries happen.

- Where DLQs exist (or don’t).

- For each core business flow (e.g., signup, checkout, ETL job):

Outcome: a short doc or diagram set that shows where money and risk concentrate.

Day 3–4: Fix the biggest cost & reliability foot-guns

- Right-size Lambda memory & timeouts for the top 10

- Use recent metrics:

- If avg execution time is 50ms and timeout is 30s, reduce timeout.

- Experiment with more memory to reduce duration where CPU-bound.

- Target:

- Timeouts within a 3–5

- Use recent metrics: